John Hume RIP

By John Battle, Commission Chair

(adapted from John’s universe article)

Sorting family papers this summer, my wife’s father’s family in Derry turned up a handwritten letter to her Uncle Eddie from John Hume written in 2001. It congratulated him on his 80th birthday and thanked him for his key role in establishing the Credit Union with him and helping make the credit union a national model. In these times when politicians across the world are held in low esteem, the death of Northern Ireland’s John Hume is a timely reminder of the potential for good in dedicated and hardworking politics committed to justice and peace. He was a man with a vision of the possibilities of peace in practice in Northern Ireland. As time passes so quickly now, three decades of the violent “Troubles” in Northern Ireland (which cost over 3,500 lives – mostly Catholic) are nearly a forgotten world away from today’s realities. The fact that our own children and grandchildren can go over to Northern Ireland and enjoy family visits without fear or restrictions worse than the virus lockdown is largely due to the lifetime peace-making efforts of John Hume.

John Hume  was not a high profile party politician yet he has emerged as one of the most important political leaders of the twentieth century; the politician who crafted the Northern Ireland Peace Process signed in 1998 for which, jointly with David Trimble, he received the Nobel Peace Prize.

was not a high profile party politician yet he has emerged as one of the most important political leaders of the twentieth century; the politician who crafted the Northern Ireland Peace Process signed in 1998 for which, jointly with David Trimble, he received the Nobel Peace Prize.

For years John Hume “kept hope of peace alive”, refusing to accept there was no workable alternative, furrowing a lonely path in the face of opposition and taking real personal risks to bring about a peaceable settlement to the violent, deadlocked Northern Ireland. Despite direct threats to his life, vandalism to his home and torching of his car he never had a police body guard or carried a gun (though all Northern Ireland politicians could). He simply insisted on an alternative to bombs and bullets. He patiently negotiated a compromise statement with Conservative Northern Ireland Secretary Peter Brooke stating, “Britain has no selfish strategic or economic interest in Northern Ireland “. He engineered an IRA ceasefire in 1994 after clandestine meetings with Gerry Adams for which Ian Paisley called him a “messenger boy for the IRA”; nationalists called him a sell-out, derided as a naive man in the middle.

But it was his insistent commitment to bringing people and communities together, rooted in courteous yet tough minded outreaching dialogue that characterised his approach. In the later words of Pope Francis he was prepared “to cross the street” for peace. He had an unshaken opposition to violence whether of the IRA, UDA, British Army or police and an unswerving commitment to peace-making built on a vision of society with human rights and democracy at the core. His belief was in an “agreed Ireland”.

John Hume was a man of language. He spent his life talking, listening, reassuring, questioning, explaining, and persuading. Meeting up with him occasionally in the House of Commons he always came across as a thoughtful man, reflecting before speaking, crafting his words deliberately but treating all those he spoke with full respect. In conversation everyone was as important and valuable to him as the leaders and Presidents he spoke with. He once commented that “political leadership is like being a teacher… It’s about changing the language of others. I say it and I say it until I hear the man in the pub saying my words back to me”. He became known in political circles for introducing “Humespeak” a vocabulary which became the language of the peace process, rooted in reconciliatory words never wavering from compromise and commitment to peace. He cited his father, echoing a practical search for solutions to everyday human problems; “you can’t eat a flag” he said. John Hume was not a crude nationalist. He was a peacemaker in the mould of Martin Luther King (“we shall overcome”) and Gandhi (” Be the change you want”).

In 2006 he was awarded an honorary degree by the Peace Studies department of Bradford University. Professor Tom Woodhouse (Professor of Conflict resolution in the Peace Studies department) in his oration at the ceremony commented “It is of course well known that he holds the Nobel Prize, but I should also point out that he is the only person in history ever to have been awarded not one but the three major peace prizes, that is the Nobel Peace Prize; the Martin Luther King Prize; and the Gandhi Award for Nonviolent Peacemaking.” He went on to say “As the architect of the Northern Ireland peace process, John Hume’s work has significance way beyond Northern Ireland itself. What he achieved there has truly global significance. It demonstrated not only the importance of conflict resolution and peace research, but also the urgent need to extend this work in the modern world.

Northern Ireland today still has dividing has walls between communities. It has yet to have a fully accepted and workable “truth and reconciliation” process to heal the wounds and lay to rest the violent suffering of the past. There is political work still to be continued. But in laying John Hume to rest, may he now rest in true peace in eternally in the community of saints and remain here a role model for present and future politicians. John Hume rest in peace.

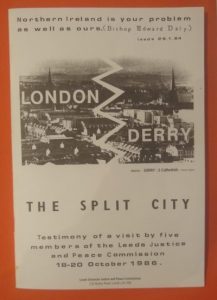

During the 1980’s the situation in N Ireland was one of the J&P Commission’s priorities. It organised a series of seminars in conjunction with the Peace Studies department at Bradford University. At our invitation, the then bishop of Derry, Edward Daly, came and preached on Peace Sunday 1984 at Leeds Cathedral. He  encouraged the Commission to make a visit to see the situation for themselves. This took place in October 1986 and the photo below is the cover of the booklet of the observations and reflections of those who undertook the trip.

encouraged the Commission to make a visit to see the situation for themselves. This took place in October 1986 and the photo below is the cover of the booklet of the observations and reflections of those who undertook the trip.

In their report they acknowledge the perseverance and determination of then Commission member Thelma Laycock (of the Cathedral parish) in making the trip come to fruition.

*****************************************